Process controls: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

p(t) refers to the controller's output while :<math> p_s </math> refers to the steady state value of the controller. :<math> K_c </math> refers to the controller gain, and e(t) is the error function. This type of controller simply responds proportionally with the error signal (which is the deviation from the setpoint). The greater the error, the greater the response. Mathematically, this first order function has no bounds, but in reality, it would reach a saturation point on both ends of the error. |

p(t) refers to the controller's output while :<math> p_s </math> refers to the steady state value of the controller. :<math> K_c </math> refers to the controller gain, and e(t) is the error function. This type of controller simply responds proportionally with the error signal (which is the deviation from the setpoint). The greater the error, the greater the response. Mathematically, this first order function has no bounds, but in reality, it would reach a saturation point on both ends of the error. |

||

While this controller would respond immediately to the error, this type of controller is susceptible to a steady-state error (or offset) following a sustained disturbance. |

While this controller would respond immediately to the error, this type of controller is susceptible to a steady-state error (or offset) following a sustained disturbance<ref name="seborg" />. |

||

====Integral Control==== |

====Integral Control==== |

||

:<math> p(t) = p_s + \frac{1}{\tau} \int\limits_{0}^{t} e(t)\text{d}t </math> |

:<math> p(t) = p_s + \frac{1}{\tau} \int\limits_{0}^{t} e(t)\text{d}t </math> |

||

:<math> \tau </math> refers to the reset time. This type of controller is primarily a response to the inherent deficiency of proportional control as this would fix the offset error. However, used by itself, the controller does not take action until the error has accumulated since the controller only responds to the total summation of the error (the integral). Consequently, this is often used in conjunction with proportional control. In addition, integral controls, even when used in conjunction with proportional control, are very susceptible to oscillations. |

:<math> \tau </math> refers to the reset time. This type of controller is primarily a response to the inherent deficiency of proportional control as this would fix the offset error. However, used by itself, the controller does not take action until the error has accumulated since the controller only responds to the total summation of the error (the integral). Consequently, this is often used in conjunction with proportional control. In addition, integral controls, even when used in conjunction with proportional control, are very susceptible to oscillations<ref name="seborg" />. |

||

====Derivative Control==== |

====Derivative Control==== |

||

:<math> p(t) = p_s + \tau_D \frac{\text{d}}{\text{d}t}e(t) </math> |

:<math> p(t) = p_s + \tau_D \frac{\text{d}}{\text{d}t}e(t) </math> |

||

This control scheme attempts to anticipate the disturbance by considering the derivative of the error. This type of anticipatory action makes a physical implementation difficult and a filter term is needed to make this controller feasible. In addition, this anticipatory scheme is also very susceptible to system noise. If the system changes slightly over a short period of term, the derivative term will be large, causing a large response. As a result, many industrial usages use a combination of all three schemes, known as a PID controller. |

This control scheme attempts to anticipate the disturbance by considering the derivative of the error. This type of anticipatory action makes a physical implementation difficult and a filter term is needed to make this controller feasible. In addition, this anticipatory scheme is also very susceptible to system noise. If the system changes slightly over a short period of term, the derivative term will be large, causing a large response. As a result, many industrial usages use a combination of all three schemes, known as a PID controller<ref name="seborg" />. |

||

====PID Controller==== |

====PID Controller==== |

||

Revision as of 23:15, 1 March 2015

Author: Samson Fong [2015]

Stewards: Jian Gong and Fengqi You

Introduction

Process control is an important part in maintaining the output of a system within a desired range by manipulating various inputs. The objective of process control is to model a system’s behavior when a certain perturbation is made. This may be an artificial perturbation or system noise or drift. Practically, process control is used to maintain the desired output (flowrates, temperature, compositions, and other properties) In addition, process control is very important to ensuring the safety of the workers and the community in which the plant is a part of. Controlling the process at a certain operating conditions (including temperature and pressure) will prevent the system from reaching dangerous levels that may cause a run-away reaction or other hazards that may harm those around the plant.[1].

This article addresses the theoretical background of process control rather than the mechanical instruments (such as valves, controllers, etc) used for the control.

Brief History

Automatic control systems dated as far back as the ancient Greeks around 300 BC when a Greek mathematician Ctesibius invented a water clock ][2]. However, formal mathematical formulations of control theory began by James Clerk Maxwell in his paper On governors in the Proceedings of Royal Society (1867-1868) [3]. The paper focused primarily on the steam engine.

Since Maxwell’s paper, the field has developed substantially and applied in a variety of fields. For instance, the Wright brothers had to develop dynamic control to sustain manned flight [4]. Control theory also played an important role in stabilizing ships and even in space travel.

Defining inputs and outputs

The first step to designing or analyzing a process control scheme is to determine the various inputs and outputs. There are three broad categories for any given system: inputs, outputs, and constants or parameters. Inputs are any factors that change with time that affect the system’s output. The output refers to the desired controlled variable. Consider this as the objective of the model. Finally, the constants or parameters are simply any variables that stay constant with respect to time that do not impact the output’s dynamics.

Inputs can further be separated into disturbance inputs and manipulated inputs. Manipulated variables refer to the quantities that are directly adjusted to control the system. Disturbance variables refer to the quantities that affect the control variable that cannot be controlled. One useful method in determining disturbance variable is to identify the manipulated variables and outputs. All other variables (not constants) are generally disturbance input variables [5].

Feedback control

Feedback control refers to a system where the controlled variable is measured while the manipulated variable is changed. Due to the delayed nature of the control scheme, a disadvantage is that the system is almost always wrong before any corrective measures are taken. However, since the output is measured directly, an accurate depiction of the output is known at all times [5].

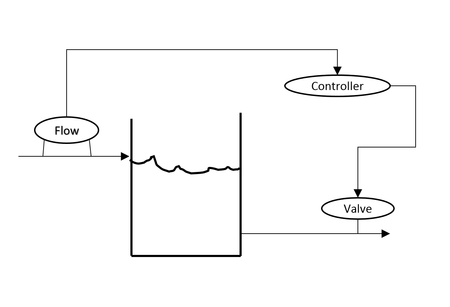

Case Study 1

The scheme above is intuitively a feedback control scheme. The level indicator will impart the information to the controller, and the controller will make the decision to whether to increase flow rate or decrease flow rate by adjusting the valve. The controller makes the decision according to the transfer function that it is calibrated with. Most practically, as the level indicator reads too high a level, the controller will open the valve in order to increase flow rate.

In this case, the disturbance input is the input flow into the surge tank, and the manipulated input is the flow rate out of the tank. Since the manipulated variable is what is being changed (via the valve), this is by definition a feedback control. Since the level of the fluid in the tank is being measured by the level indicator, it is the controlled variable.

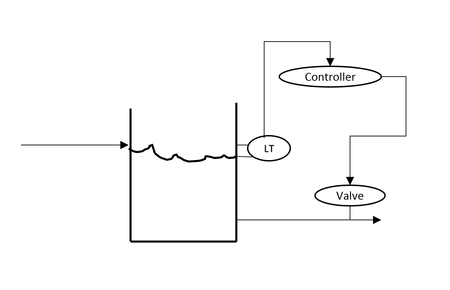

Case Study 2

The scheme above is less intuitive. Since the valve is fixing the flow into the tank rather than out of the tank, it is common to misclassify this scheme as feedforward. However, careful consideration of variables show that the valve makes the flow into the tank the manipulated variable while the flow out simply becomes the disturbance variable. Similar to the first scheme, the controlled variable (the level) is still being measured. As a result, this is still a feedback control by definition. Note, that the position of the variables in the physical setup has little bearing on the classification (hence analysis) of the system.

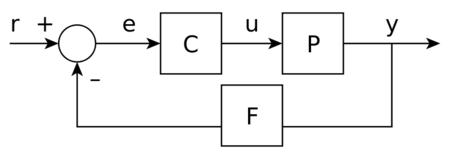

Alternative depiction

This is an alternative depiction of a generic feedback control. In this diagram, information is treated equally as material flow where as previously, some diagrams distinguish the two by using dotted lines for information flow and solid lines for material flow. The main idea of this diagram is not to show the physical system, but the way the controller is interacting with the different elements.

This is useful in determining the transfer functions of the controller since the diagram depicts not only the different pieces of information that are flowing (from the controller C to the plant P which flows to the sensor F) but also the order in which they come in. In addition, two adjacent boxes are equivalent to multiplying the two transfer functions. As a result, a simple rearrangement will yield a transfer function that is representation of the system.

Quantitative Discussion of Feedback Control

Below are different schemes for feedback controller that decides how much of the valve is opened (in the previous examples) or how much to respond to the current pertubation. As one can see from the alternative depiction, feedback control is considered a closed-loop system as the information makes closed loop.

Proportional Control

p(t) refers to the controller's output while : refers to the steady state value of the controller. : refers to the controller gain, and e(t) is the error function. This type of controller simply responds proportionally with the error signal (which is the deviation from the setpoint). The greater the error, the greater the response. Mathematically, this first order function has no bounds, but in reality, it would reach a saturation point on both ends of the error.

While this controller would respond immediately to the error, this type of controller is susceptible to a steady-state error (or offset) following a sustained disturbance[5].

Integral Control

- refers to the reset time. This type of controller is primarily a response to the inherent deficiency of proportional control as this would fix the offset error. However, used by itself, the controller does not take action until the error has accumulated since the controller only responds to the total summation of the error (the integral). Consequently, this is often used in conjunction with proportional control. In addition, integral controls, even when used in conjunction with proportional control, are very susceptible to oscillations[5].

Derivative Control

This control scheme attempts to anticipate the disturbance by considering the derivative of the error. This type of anticipatory action makes a physical implementation difficult and a filter term is needed to make this controller feasible. In addition, this anticipatory scheme is also very susceptible to system noise. If the system changes slightly over a short period of term, the derivative term will be large, causing a large response. As a result, many industrial usages use a combination of all three schemes, known as a PID controller[5].

PID Controller

This scheme is a combination of the previous three schemes. This scheme employs all the advantages of the three schemes. However, it also inherits the disadvantages. Most notably, the problem with derivative controllers where it would respond rapidly to a noisy system. As a result, each controller is often tuned specifically to the system on hand by tuning each parameter or by adding terms to the control algorithm [6].

Feedforward control

Feedforward control refers to a system where the disturbance variable is measured and the controlled variable is not measured. The reason is feedforward control is a predictive control scheme where only an input is measured, and the control system will predict the appropriate control scheme to ensure the desired output occurs [5].

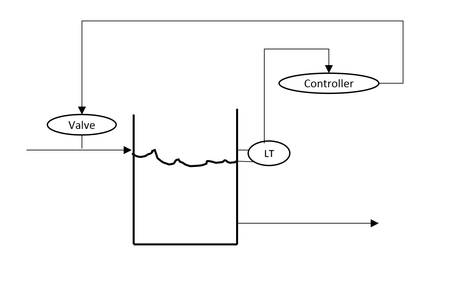

Case Study

This scheme share many similarities with the second feedback scheme. It also has the flow into the tank as the manipulated variable while the flow out is the disturbance variable. However, this scheme does not show that the level is being measured. Since the controlled variable is not measured, it is classified as a feedforward scheme.

Industrial Usage

Ideally, a perfect feedforward control will be able preemptively adapt to any disturbances to the system and correct any disturbance quickly. However, any imperfection whether in the model or the mechanical implementation would lead to undetected behavior in the output.

In most industrial applications, feedforward control is usually not used by itself. However, it is often used in conjunction with feedback control in order to correct the main disadvantage of the feed forward control. [1]

References

- ^ a b G.P. Towler, R. Sinnott Chemical Engineering Design: Principles, Practice and Economics of Plant and Process Design Elsevier, 2012

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica: Ctesibius. "Greek physicist and inventor, the first great figure of the ancient engineering tradition of Alexandria, Egypt."

- ^ Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. "On Governors"

- ^ "Flying Machine patent." Patents. Retrieved: September 21, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f D.E. Seborg, T.F. Edgar, D.A. Mellichamp, F.J. Doyle Process Dynamics and Control Wiley, 2011

- ^ Daniel E. Rivera , Manfred Morari , Sigurd Skogestad ACS Publications. "Internal model control: PID controller design"

![{\displaystyle p(t)=p_{s}+K_{c}\left[e(t)+{\frac {1}{\tau }}\int \limits _{0}^{t}e(t){\text{d}}t+\tau _{D}{\frac {\text{d}}{{\text{d}}t}}e(t)\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a0890cac53eb24e7ae70bd9b059a29900757c0b8)