Pressure changer

Authors: Kedric Daly [2016]

Stewards: David Garcia, Fengqi You

Date Presented: February 5, 2016

Introduction

Pressure changers are any piece of equipment where the main goal is to increase or decrease the pressure of a stream. Typically, pressure changers are used mostly for increasing pressure, due to the fact that pressure losses occur within a system due to friction with pipes, pipe bends, valves, and other pieces of equipment [1]. Lowering the pressure of a system can also be useful however, such as to favor the products of a chemical reaction through Le Chatelier's principle. It is important however to ensure proper pressure is maintained throughout a chemical process so that blowback does not occur, and any fluids actually reach their destination as expected, at the proper conditions.

There are many different types of modeling software for chemical processing, Aspen HYSYS, and Aspen Plus being well known. Like any piece of process equipment, it is necessary to specify a number of independent variables in order for the simulation to converge and produce unknown values. There are different combinations of independent variables that will suffice and cause the model to converge. Different parameters of the pump or compressor can also be specified, such as efficiency, which will impact the results of the simulation. It is therefore important to ensure the equipment is correctly specified to ensure accurate results.

Pumps

Pumps do work on fluids, causing them to increase in pressure at a constant volume, due to the assumption that liquids that enter pumps are mostly incompressible. For more information on different types of pumps and other pressure changers, see Process hydraulics.

To find the power outlet required by a pump to pressurize a fluid, an energy balance can be done on the system. The result is the mechanical balance equation, below:

Where is the power required, is the mass flow rate, is that shaft work, is the velocity of the fluid, describes the flow in the system (0.5 for laminar, 1 for turbulent), is the gravitational acceleration, is the change in height, is the constant volume PV work done, and is the force acting on the fluid. Each grouping deals with different aspects of the fluid flow. The first term deals with the kinetics, the second term with the statics, the third term with the pressure head, and the fourth term with the viscous losses. [2] It should also be noted that a pressure head is the height of a fluid that results in an equivalent pressure via the relation.

While the mechanical balance equation can be used to find the outlet power required, no pump is 100% efficient. The efficiency, , of a pump is defined as:

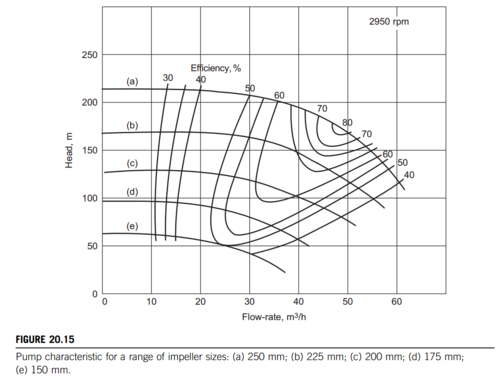

The efficiency of a pump is related to the pressure head and the fluid flow rate because the work can be converted to either a higher velocity or a larger pressure head.[2]. Manufacturers often supply characteristic pump curves in order to inform their customers which pumps will meet their needs. Using these types of curves, it can be seen where the best operating range is for a pump in order to maximize efficiency, and therefore minimize losses in the system. An example curve can be seen below.

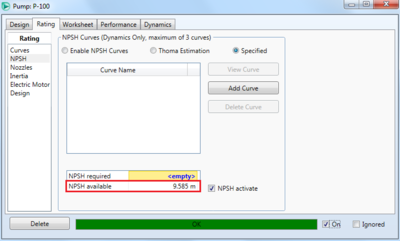

Another important consideration for pumps is that a Net Positive Suction Head () must be maintained within the pump, in order to avoid cavitation.[3] Cavitation occurs because as fluid enters a pump, frictional losses near the pump entrance cause a pressure drop, leading to a minimum pressure somewhere in the pump, and if the fluid is close to saturation, bubbles can form within the pump[3]. Specifically, to avoid cavitation, the available NPSH () must exceed the required NPSH (), which is specified by the manufacturer of the pump because depends on the pump design. The can be found by using equation (20.21) in Towler, below: [1]

Where is the pressure above the liquid in the feed vessel, is the height of the liquid above the pump section, is the pressure loss in the suction piping, is the vapor pressure of the liquid at the pump suction, is the density of the liquid, and is the acceleration due to gravity. Regardless of what is, the from the above equation must exceed it to avoid cavitation.

Modeling with HYSYS

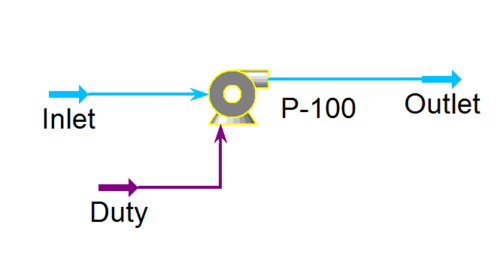

Pumps can be modeled in Aspen HYSYS using the pump unit operation. Modeling can be done because while the specific thermodynamics, physical properties, and kinetics may differ from process to process, the conservation equations remain the same for similar process units, pumps included.[4]. In order to model a pump, it pump requires an inlet stream, an outlet stream, and an energy stream, as can be seen in the figure below.

In order for any useful information to be gleaned from the model, certain combinations of specifications must be made. There are multiple ways of going about the specification process, depending on what information is known and what information the modeler wants to know. In general, two of the three steams will need to be specified, in order to calculate the third stream. For example, specifying the inlet and outlet will allow for the pump duty to be calculated. This is a common specification because processing conditions are often known, but the modeler would want to know how powerful of a pump they will need for this specific pump, so they need to know the pump duty.

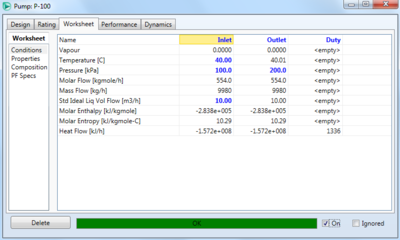

One basic example is if we want to pressurize a stream of water from 1 bar and 40C to 2 bar, and see how much energy the pump will require to do so. To specify the inlet stream, double click on it it HYSYS, and specify the molar flow rate, and other process variables, as well as the stream composition. In this example, the non-random two liquid (NRTL) fluid package is used, with the temperature of the inlet stream specified as 40C, the pressure as 1 bar (100 kPa), the mass flow rate as 10 m3/h, and a water mole fraction of 1. Then, if the outlet stream is specified to be at a pressure of 2 bar (200 kPa), there is enough information for HYSYS to calculate the pump duty, as well as the other outlet stream conditions via mass and energy balances. The specifications can be seen below, and the inlet and outlet stream should change from a light blue to a dark blue in HYSYS when they are specified and solved correctly. HYSYS also calculates the , which can be seen in the rating tab of the pump and is 9.585 m in this case.

| Change in color observed on pump when properly specified | |||

The result is that the pump requires 1336 kJ/h, which equates to 0.3711 kW for the pump, indicating this is a fairly low power operation to perform.

Compressors

Valves

Piping

Summary

When modeling pressure changers with computer software, it is important to not over-specify them, as for any other piece of equipment. Failing to include them in the final process simulation may lead to odd results, such as a negative pressure drop through a heater or cooler in order to meet pressure or temperature specifications on a material stream. Should this situation occur, a pump or compressor should be added to ensure that a physically possible pressure drop takes place in the processing equipment. Pumps and compressors will use electricity to perform their pressure changes, and if many pumps or a large compressor is used in the process, this can have impacts on the process economics, so it is important to model pressure changers when designing a chemical process.

References

- ^ a b c G.P. Towler, R. Sinnott, Chemical Engineering Design: Principles, Practice and Economics of Plant and Process Design, Elsevier, 2012.

- ^ a b YA Hussein. Pressure Changers. Available at http://www.just.edu.jo/~yahussain/files/Pressure%20Changers.pdf Accessed February 3, 2016

- ^ a b R.T. Turton, R.C. Bailie, W.B. Whiting, J.A. Shaeiwitz, Analysis, Synthesis, and Design of Chemical Processes, Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, 2003.

- ^ W.D. Seider, J.D. Seader, D.R. Lewin, Process Design Principles: Synthesis, Analysis, and Evaluation, Wiley: New York, 2004.